Introduction

Regression is the task of learning the relationship between input data and corresponding output data, and predicting the output for unseen inputs. This article uses linear regression as an example to compare four representative parameter estimation methods: least squares, maximum likelihood estimation, MAP estimation, and Bayesian estimation, and explains their differences and characteristics.

As the model, we consider a linear combination of basis functions \(\phi(x)\), which are nonlinear functions of the input \(x\). With \(w\) as the model parameters (weights) and \(\epsilon\) as the error, the model is:

\[ y = \Phi w + \epsilon \]Here, \(\Phi\) is the design matrix, where each row contains the basis function vector for a data point.

1. Least Squares Estimation

Least squares finds the parameters \(\hat{w}\) that minimize the sum of squared errors \(S(w)\) between the model predictions and the actual target values.

\[ S(w) = (y - \Phi w)^T (y - \Phi w) \]Setting the derivative of \(S(w)\) with respect to \(w\) to zero yields:

\[ \hat{w}\_{LS} = (\Phi^T \Phi)^{-1} \Phi^T y \]This has an analytical solution, making computation very fast. However, it is prone to overfitting when the training data is limited or the model has high degrees of freedom.

2. Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

MLE finds the parameters \(\hat{w}\) that maximize the probability of observing the data (likelihood).

Assuming the error term \(\epsilon\) follows a Gaussian distribution with mean \(0\) and variance \(\sigma^2\), the conditional probability of the target \(y\) becomes a Gaussian with mean \(\Phi w\) and variance \(\sigma^2\).

\[ p(y | w, \sigma^2) = \mathcal{N}(y | \Phi w, \sigma^2 I) = \frac{1}{(2\pi\sigma^2)^{N/2}} \exp\lbrace-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}(y-\Phi w)^T(y-\Phi w)\rbrace \]We maximize the log-likelihood:

\[ \ln p(y|w) = -\frac{N}{2}\ln(2\pi\sigma^2) - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2}(y-\Phi w)^T(y-\Phi w) \]Maximizing the log-likelihood is equivalent to minimizing the squared error term on the right. Therefore, under a Gaussian error assumption, MLE yields the same solution as least squares.

\[ \hat{w}\_{ML} = (\Phi^T\Phi)^{-1}\Phi^{T}y \]3. MAP Estimation (Maximum A Posteriori)

MAP estimation is a general framework for suppressing overfitting. It treats the parameters \(w\) as random variables and introduces a prior distribution \(p(w)\). Using Bayes’ theorem, it finds the \(\hat{w}\) that maximizes the posterior distribution \(p(w|y)\).

\[ p(w|y) = \frac{p(y|w)p(w)}{p(y)} \propto p(y|w)p(w) \]Assuming a Gaussian prior with mean \(0\) and covariance \(\alpha^{-1}I\) for \(w\), this encodes the prior belief that the weight values should be close to zero, acting as regularization that penalizes large weights.

\[ p(w|\alpha) = \mathcal{N}(w|0, \alpha^{-1}I) \]The MAP estimate \(\hat{w}_{MAP}\) is:

\[ \hat{w}\_{MAP} = (\Phi^T\Phi + \frac{\beta}{\alpha}I)^{-1}\Phi^{T}y \]where \(\beta = 1/\sigma^2\). This has the same form as ridge regression (L2-regularized least squares), and the regularization term \(\frac{\beta}{\alpha}I\) ensures stable solutions even when \(\Phi^T\Phi\) is not invertible, while suppressing overfitting.

4. Bayesian Estimation

Least squares, MLE, and MAP estimation all find a single optimal value for \(w\) (point estimation). However, this approach cannot express uncertainty about the parameters.

Bayesian estimation does not seek a single point estimate but instead computes the full posterior distribution \(p(w|y)\), representing the probability distribution over all possible values of \(w\) given the observed data.

With the Gaussian prior and likelihood used in MAP, the posterior is also Gaussian (conjugacy):

\[ p(w|y) = \mathcal{N}(w | \mu_N, \Sigma_N) \]where the posterior mean \(\mu_N\) and covariance \(\Sigma_N\) are:

\[ \mu_N = (\Phi^T\Phi + \frac{\beta}{\alpha}I)^{-1}\Phi^{T}y \]\[ \Sigma_N = (\beta\Phi^T\Phi + \alpha I)^{-1} \]For prediction on a new input \(x_*\), we integrate over all possible \(w\), weighted by the posterior probability. This is called the predictive distribution.

\[ p(y*\* | x*\_, y) = \int p(y\_\_ | x\_\*, w) p(w|y) dw \]The predictive distribution provides not only the mean prediction but also the variance (confidence interval) indicating prediction uncertainty.

Experimental Results

- Data: 15 training points generated from \(y = \sin(2\pi x)\) with added noise

- Basis functions: 9th-degree polynomial (\(f_j(x) = x^j, j=0, ..., 9\))

- Hyperparameters: \(\alpha=1.0, \beta=10.0\)

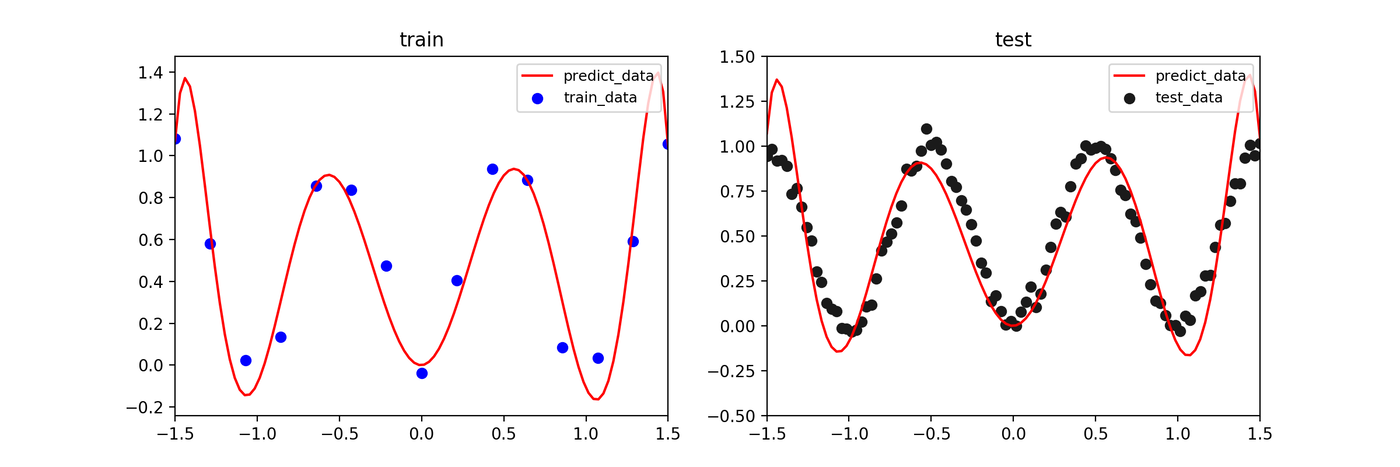

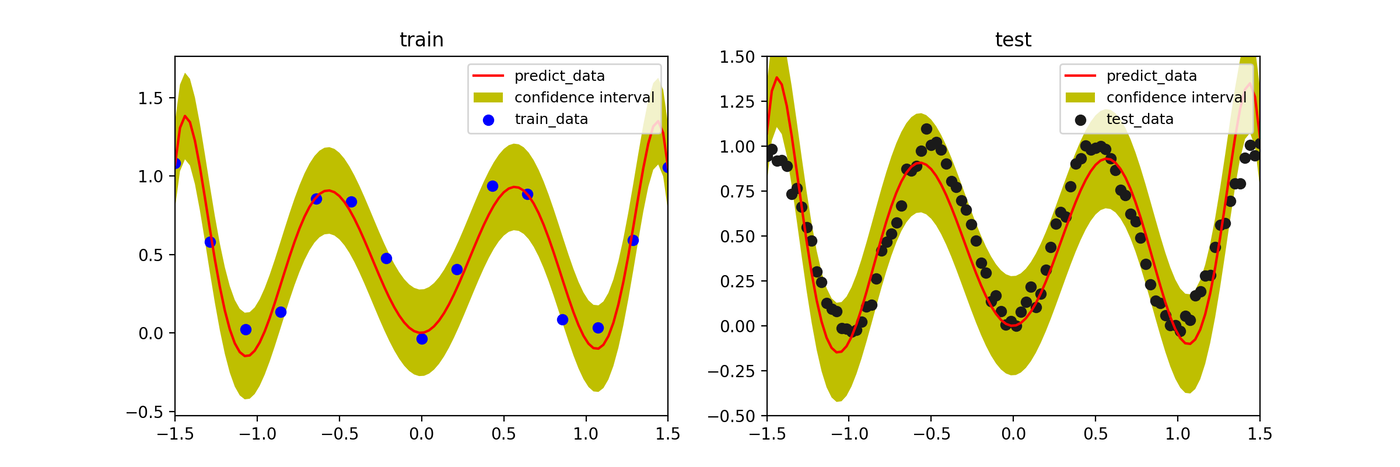

Least Squares / Maximum Likelihood Estimation

The model tries to fit the training data closely, causing large oscillations in regions without data – a clear case of overfitting.

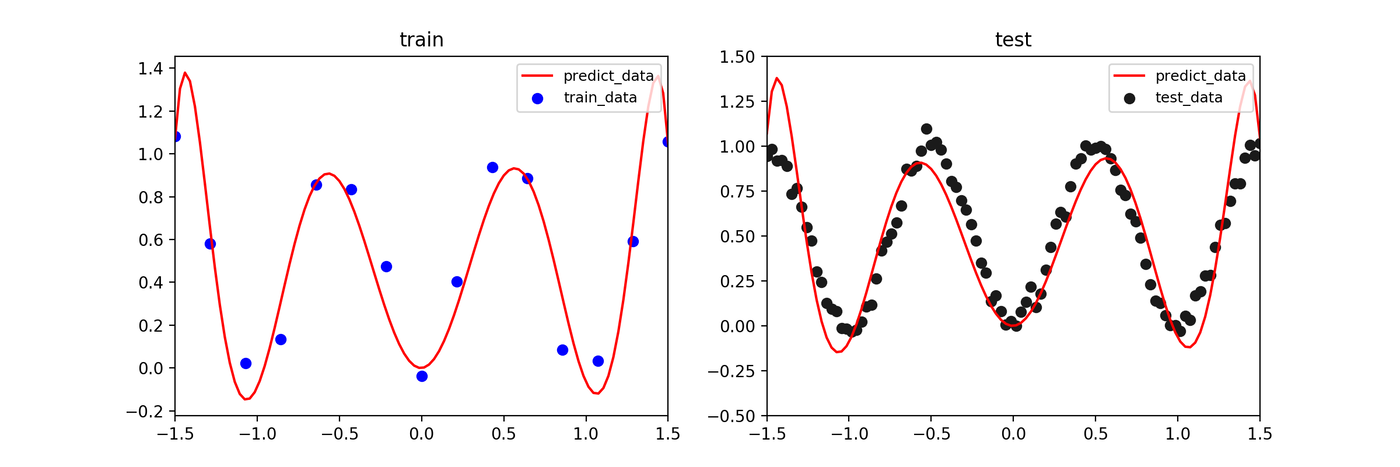

MAP Estimation

The prior distribution (regularization) suppresses overfitting, yielding a smoother prediction curve.

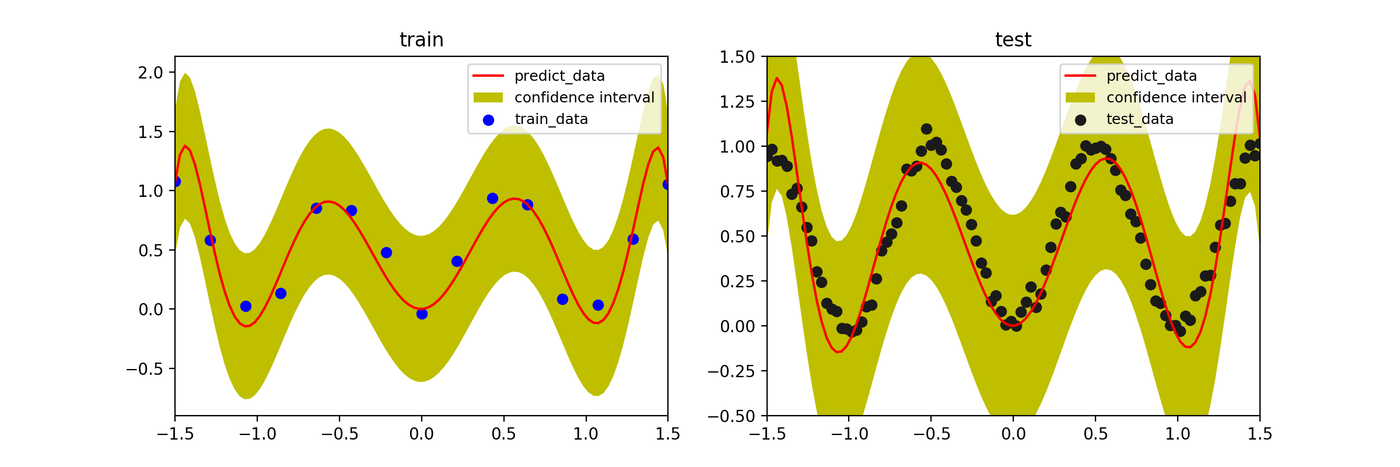

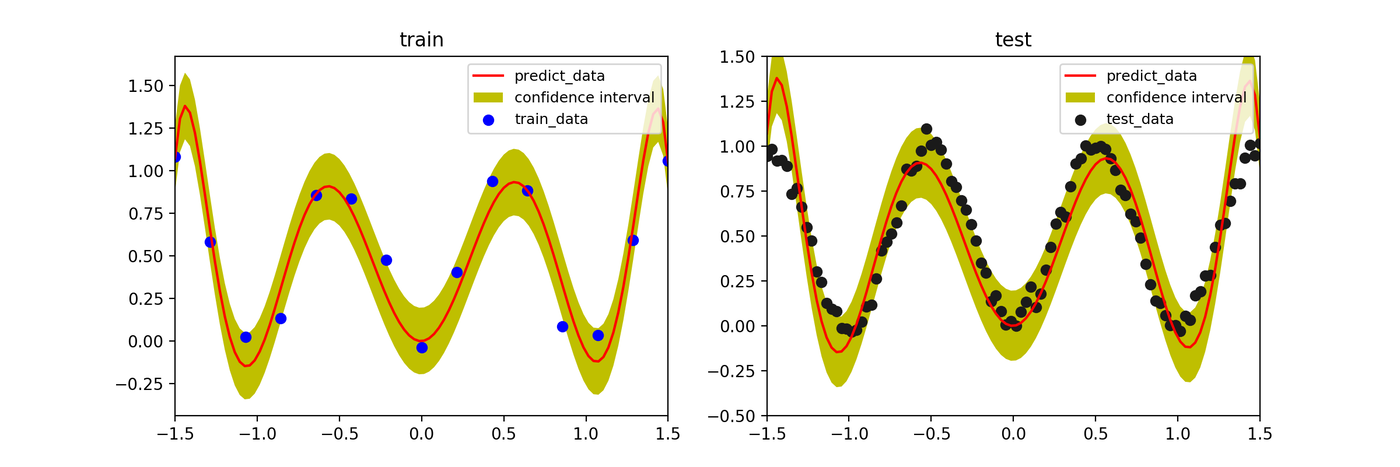

Bayesian Estimation

In addition to a smooth prediction (mean, solid line) similar to MAP, the prediction uncertainty increases in regions with less training data, as shown by the widening confidence interval (blue shaded area).

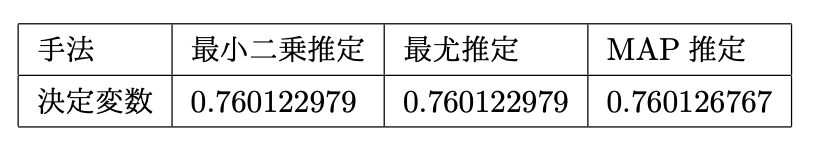

Model Evaluation (Coefficient of Determination \(R^2\))

The coefficient of determination indicates how well the model fits the data (closer to 1 is better). MAP and Bayesian estimation (mean) achieve higher scores than least squares.

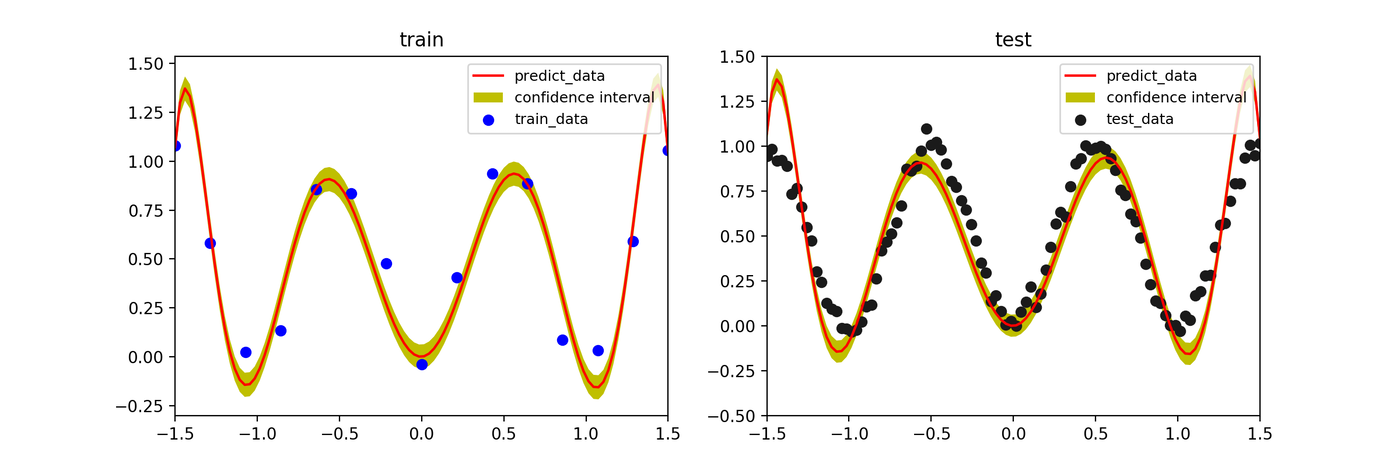

Effect of Hyperparameter \(\beta\)

In Bayesian estimation, increasing the likelihood precision parameter \(\beta\) (inverse noise variance) causes the model to fit training data more tightly. When \(\beta\) is too large, the confidence interval narrows and the result approaches overfitting.

- \(\beta=50\)

- \(\beta=100\)

- \(\beta=1000\)

Summary

- Least Squares / MLE: Simple and fast, but prone to overfitting.

- MAP Estimation: Introduces a prior (regularization) to suppress overfitting.

- Bayesian Estimation: Accounts for parameter uncertainty and provides confidence intervals for predictions. It gives richer information, such as increasing uncertainty in data-sparse regions.

References

- C.M. Bishop, “Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning,” Springer (2006)

- Atsushi Suyama, “Introduction to Machine Learning with Bayesian Inference,” Kodansha (2017)